Thunder Glacier

Ski Descent

A Hidden Classic

We’re lucky to have Mount Baker as our namesake and main office. Complex, heavily glaciated, and wonderfully positioned in the North Cascades, Koma Kulshan stands at only 10,781 feet, yet radiates a BIG mountain impression. The mountain receives some of the largest snowfall totals in the world and hosts numerous classic ski mountaineering objectives. I’ve been exploring this topography for nearly four years and it continues to deliver amazing opportunities for adventure, such as skiing the Thunder Glacier.

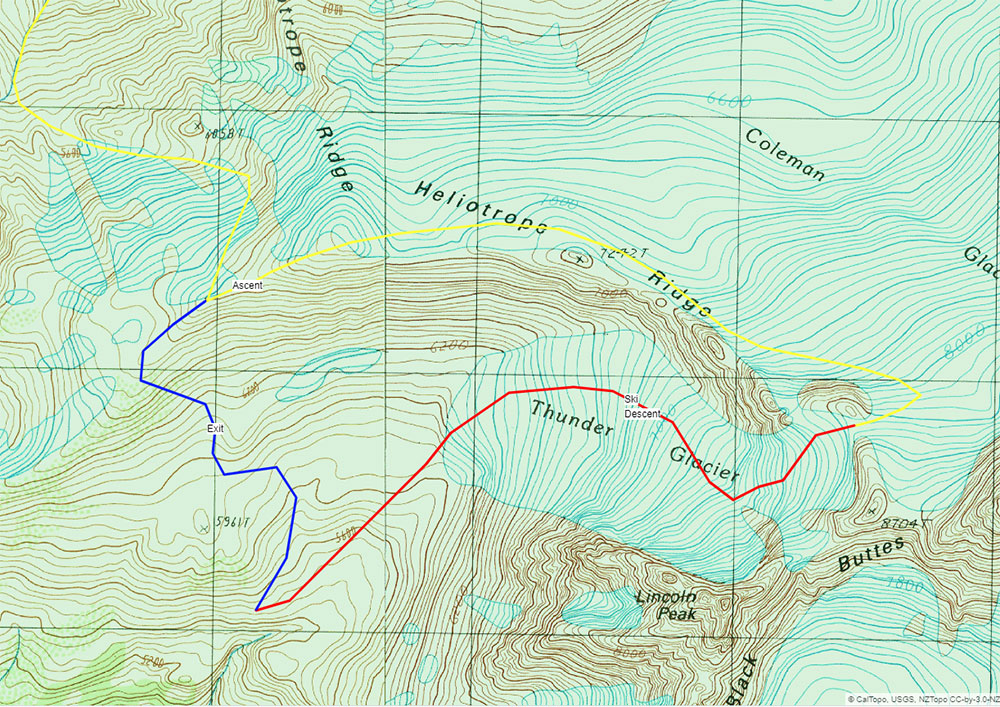

The Thunder Glacier had been on my radar as a ski descent for several winters. It’s a striking line that’s often hidden while climbing the main routes. The Thunder Glacier is tucked between the jagged walls of Lincoln Peak and Heliotrope Ridge. Both flanks are characterized by crevasses and seracs, leaving a perfectly plumb fall line descent right down the middle. On March 15th 2020, as “normal” daily life was about to come to a screeching halt, we set off to snag what would be one of the last missions of our season.

Glacier Creek Road Access

At 5:00 am the crew piled into my Tundra with snowmobiles in-toe. As we rolled out of Bellingham and down HWY 542, the excitement for the day started to build.I love these big days in the mountains. Forty-five minutes later, we found snowline on the Glacier Creek Road ◙. Five miles remained between us and the Heliotrop Trailhead ◙. Time to unload the sleds and figure out how to get six people up the road with two machines.

We had two options: we could shuttle and do two trips from truck to trailhead or we could double tow and get everyone up in one push. Shuttling would be easier on the snowmobiles and the legs; towing would save us an hour. I have a tendency to get a little over-stoked from time-to-time, especially when we have the opportunity to get the Baker Mountain Guides squad together on a rare sunny pow day. That and the fact that we were heading out for a big day made us decide to tow. A short 15 – 20-minute ride and we’d be on skis heading up the mountain. What could go wrong

This was our first season with consistent access to snowmobiles, necessary toys to execute our new program: Twin Sisters Backcountry Skiing. In efforts to execute a smooth day of guiding on sleds, the past month was dedicated to, well, making mistakes. We learned how to get stuck, get unstuck, rig gear poorly, and rig gear properly. The devil is in the details and we still had a few lessons to learn.

The zone is popular amongst local snowmobilers and the road typically boasts a packed sled track. Packed roads require the use of scratchers. These little rods of metal scratch the firm snow, kicking up enough debris to keep the engine cool. Fueled by excitement, we overlooked these little buggers and took off before putting them down. Nearly halfway, both drivers smelled trouble, literally. The sleds were overheating. We stopped, packed the tracks with snow and waited roughly 20 minutes for things to cool down. The hot engine melted and warped one of the drive belts. With snowmobiles you just have to roll with the punches; they break, get stuck, overheat, it’s just the name of the game.

By 7:30 am we made it to the trailhead. Psyche levels were high.

Coleman Glacier Approach

We left the snowmobiles behind and started the 3000-foot ascent up Grouse Creek ◙ to gain Heliotrope Ridge ◙. The morning was cold and calm as we toured through the old-growth forest. At treeline, we got our first look at the upper mountain. We observed active wind transport off the ridgelines giving us some concern for the conditions to come. However, the protected slopes lower on the mountain harbored perfect cold smoke pow. We continued, knowing that no matter what happened, we’d enjoy some fantastic skiing.

From the top of Heliotrope Ridge the views were amazing. To the south and west, we could see the Twin Sisters Range and the San Juan Islands. To the north, Canadian peaks littered the horizon. The Thunder Glacier was positioned directly in front of us with Mount Baker’s stoic presence looming in the background.

The south wind was stronger than we expected. Fortunately, the jagged spires of Lincoln Peak ◙ provided some protection for the route. Ski mountaineering is a game of margins. The deck was stacked in our favor with an experienced team, clear skies above, and the option to spin at any time. After some deliberation, we decided to continue.

We dropped onto the Football Field ◙, a distinct feature on the Coleman Glacier ◙. Here, we donned harnesses and crevasse rescue gear. Another 1000 feet of climbing brought us to the base of the impressive North Face of Colfax Peak ◙. From here the route takes a sharp right turn off the Coleman for the final push to the top of the Thunder Glacier.

The winds were gusting up to 40 mph with sustained speeds in the 20’s as we crested over the saddle. When we peered down the other side things didn’t add up. We had over-shot the Thunder Glacier by a hundred feet and found ourselves looking out over the Deming Glacier ◙. A short five-minute downward traverse would lead us to the upper headwall of the Thunder Glacier and the proper start of the descent.

Thunder Glacier Ski Descent

12:30 pm. Standing on top of the route it was clear that we needed to avoid the Thunder Glacier’s upper headwall. Excited and nervous, we weighed our options. The snow conditions just weren’t right for terrain that steep. To maintain our margin for error, we skied down the ridge to a saddle 500 feet below. This allowed us to take advantage of a low angle entrance onto the Thunder Glacier.

The skiing on the ridge was pretty bad. Variable and wind affected snow made for an exciting start to the descent. There was still hope that we would find better conditions lower down where the snow was protected from the strongest winds. As soon as we dropped off the saddle and onto the Thunder Glacier, the snow conditions improved. Our smiles grew large in anticipation of the turns to come.

We skied short pitches through some lower angle terrain, feeling out the conditions. As we approached a steeper and more broken section of the Thunder Glacier, a small, shallow wind slab popped on a steep convexity and ran down into a large crevasse. We set up for a long pitch of skiing through the crux of the route. We descended one at a time. It skied like a dream; beautiful boot-top pow down a 35-degree apron in a wild position. Like I said before, I love these big days in the mountains.

Everyone relaxed a bit as we paused below the crux to catch our breath and take it all in. Finally, we continued down the remaining 1,400 vertical feet of nearly perfect, untouched powder only stopping to look back in disbelief at the stunning terrain. For the majority of the line, we were in the shadow of Lincoln Peak. Near the bottom, we popped out into the sun and stopped for a much-needed break to refuel. Looking back at the Thunder Glacier we noticed that almost all of our tracks were gone. The wind quickly reset the landscape and it was as if we were never there. The impermanence of it all – the tracks, our presence – it was perfect.

Before long it was time to pack up and start our final climb of the day. The descent drops you into another basin, leaving a mean 1,200-foot climb back to the top of Grouse Creek. Despite the wind and fatigue, the team made quick work of the climb, fueled by accomplishment. Soon enough, we were transitioning for another 3,000 feet of powder back to the snowmobiles.

Thunder Glacier Route Profile:

- Total Distance – 8.5 Miles

- Trailhead Elevation – 3650 feet

- Top of Route – 8570 feet

- Elevation Gain – 6100 feet

- Thunder Glacier Descent – 3070 feet

Backcountry Run Lists

Preparing for Travel in Avalanche Terrain

One of the most commonly overlooked aspects of decision making in avalanche terrain is pre-trip preparation. Most backcountry skiers and snowboarders do a pretty good job of looking over the avalanche report in the AM, and are generally familiar with the hazard rating for the day. However, the point is to apply the hazard rating to terrain, and avoid areas that can produce an avalanche.

AIARE – The American Institute of Avalanche Research and Education – has a great pre-trip checklist available in their ubiquitous “Blue Book.” The pre-trip checklist helps users assess the hazard rating, avalanche problems, snowpack structure, weak layers, and weather factors that could contribute to, or change the avalanche hazard. Most of this information is available in the daily avalanche bulletin, local weather reports, and weather station data. However, the next step is to anticipate where hazard may exist in the terrain you are planning on touring. This is the most important part.

Operational Backcountry Run Lists

Most professional ski guides and avalanche instructors use what is known as run lists to assess terrain before going into the field. To be honest, it’s not overly complex, but it does require some amount of formal avalanche training. The fact is that recreational skiers and snowboarders can only benefit from taking a few minutes before their tour to think critically about hazard and terrain.

Run lists create a structured process for assessing terrain. They often include maps, photos, satellite imagery, and other resources with common runs drawn in and labeled. Maps help us determine distances, elevation changes, and slope angles. Imagery allows us to build familiarity with terrain, and identify areas of concern in much greater detail. Labels, or names, allow us to communicate our terrain choices clearly. The goal is to sit down before a day of backcountry skiing or snowboarding, assess the avalanche hazard, and rate each potential run as either open or closed. Once in the field, further observations can be used to close open runs. However, a run that is closed at any point cannot be re-opened. Those are the rules.

As a backcountry ski and avalanche education operation, Baker Mountain Guides is responsible for many decisions made by many of our guides on a daily basis. Run lists work by limiting emotion in the decision-making process. Any decision that we make in the field will have an emotional component, and emotions can get us into trouble. For run lists to be effective, all potential runs must be rated, and ratings must be respected. By rating all runs in a particular zone, we create many options to choose from, which allows us to craft exceptional experiences for our clientele with a high degree of confidence. Conversely, by closing runs before and during a tour, we can assure that we will not make spontaneous, emotional decisions. We may be guides, but we are also human.

Mount Baker Backcountry Ski Map

These are tools and techniques that can be easily employed by recreational skiers and snowboarders with level 1 avalanche training. However, to relate the avalanche hazard to terrain, you need to have a run list to work with. Baker Mountain Guides has spent years developing a run list for the Mount Baker Backcountry, and this summer, we worked with Fall Line Publishing to produce the Mount Baker Backcountry Ski Map. The Mount Baker Backcountry Ski Map is waterproof, tearproof, and small enough to be easily carried in the field. It covers both Bagley Lakes Basin and the Shuksan Arm, which are two exceptional and accessible backcountry venues near the Mount Baker Ski Area. Best of all, it contains both maps and photos of many common runs, which have been numbered and named. Finally, it offers users the ability to rate each run as either open or closed. The Mount Baker Backcountry Ski Map is provided to students who participate in a Baker Mountain Guides avalanche course.

Avalanche Education

Again, we cannot overstate the importance of avalanche education and mentorship. Run lists are no guarantee of safety. Decisions regarding which runs to open or close are the sole responsibility of the user. Formal avalanche training is necessary to effectively assess avalanche hazard and relate the hazard to terrain. Very few decisions in the backcountry are black and white, and good judgment before and during a backcountry tour is mandatory for a successful day. Run lists are just another very small part of a very large puzzle.