Reimagining

Recreation

Reimagining Recreation

The deer sees me before I see it. This is usually how it goes. Sometimes they bolt, sometimes they stare at me, frozen, waiting for anything to move. I’ve made an art out of courting these deer, trying to see how much of their trust I can earn. Oftentimes, I’ll kneel down, attempting to be as unassuming as possible, but today I need to walk by. I can feel the deer’s eyes and ears on me. A normal walk would not suffice, no no — this required the fox walk. It has nothing to do with how a fox walks, but it’s a certain way of moving across the land. It’s best done barefoot and perhaps with your eyes closed. Basically, you put your heel down first and then slowly feel each step with all of your senses. It can’t be done quickly, which is why it’s perfect for walking past a tentative deer. I don’t have my daughter Josie with me today, but she loves the fox walk. She hasn’t quite mastered the slow and quiet part yet, but she is only three. This is how I spend my days now. This is my recreation.

Recreation didn’t always look like this for me. In our modern culture, recreation typically implies “refreshing oneself by some amusement.” The root of recreation, recreare, means “to refresh, restore, make anew, revive, or invigorate.” Like many of you, I’ve spent the last twelve weeks of this pandemic wandering and exercising near my home. I wander, with longing and deep grief for a more meaningful connection with the land. I spend these days reimagining recreation.

Why am I reimagining recreation? Imagination feels like a lost art to me, abducted around the time I learned the scientific method. Imagination is the conversation between me and the mountain, the conversation between me, the ice worms, and the spider in the snow; The conversation between me and the wind, and the conversation between me and the wolverine. Now before you all think I’ve gone mad, think back to when you were a kid playing outside. Try to remember a time when you were in your own world making mud pies, building stick houses, or tending to wounded animals. A time when if someone called your name, you likely wouldn’t have heard them because you were so deep in your world. That feeling you had with the mud, the stories you told about the stick house, and the conversation you had with the wounded animals – those are conversations tended by your imagination. And by imagination, I don’t presume to mean those conversations are made up, quite the opposite in fact. Those conversations are the most real conversations you might ever have had. Moments when we were truly listening and being listened to.

Now that I’ve got you imagining again, I’m sure you’re wondering what this might have to do with recreation?

My relationship with recreation was not always so reflective. Before COVID, before my injuries, before having a baby, recreation was my entire life. And not the kind of recreation I describe above, but rather recreation as a means of exercise, distraction, and amusement.

I used to work as a consultant in an office and I would literally spend my days planning for my weekend adventures, trying to optimize weather and routes, calculating how tired John was going to be coming off Rainier and how much I was going to have to bribe him to go back into the mountains with me. I would come back to work exhausted from the weekend, looking at pictures from the last adventure to survive the next work week. I climbed a great many mountains. I burned hundreds of thousands of calories, ran hundreds of miles. To say this was all recreation meant to me would not be the complete truth. Each adventure, each mile, and each trail rooted me in something beyond my own Self, I just didn’t know it at the time. I was just trying to survive my life.

Perfectly Imperfect

The mountains saved me: they showed me myself, showed me my bones, showed me my roots. They reminded me of what I had forgotten along the way. They also broke me. Well… let’s be honest, I broke me. I had zero capacity to listen to my body. I could hear it loud and clear but refused to listen because the allure of the mountains was too tempting. I’m now blessed (and forced by means of injury, kids, and age), to offer my attention to my relationship with recreation and the mountains. In offering my attention, I’m imagining a different way of climbing mountains. I’m imagining being in a relationship with the wild places we wander through to reach the summits. I’m asking myself what that looks like, sounds like, smells like, and feels like. I’m asking myself what speed in which I travel will allow me to cultivate that relationship with these wild places. I’m asking myself why reaching the summit matters. And I’m asking these wild places and beings what I can offer back. Perhaps Martin Shaw is correct in offering that…

What the world truly seeks is to be admired by us.

I’m not perfect. There are plenty of days that I am rushing through a hike or bike ride to get home to pick Josie up and miss all those moments to be in relationship with that particular place — and that’s ok. What I’m imagining is that if each of us, at different times, offered our attention to the places we wander through and each offered something back – a prayer, a song of gratitude, a smile of acknowledgment, a story, tears of laughter or grief – that the wild places would be tended to, all the time. That’s what I’m imagining.

Now, I own a mountain guiding service. I sell recreation. I sell fun, even if it is Type II fun. We encourage people to get outside, to move across the lands, to explore, and help them achieve their goals. We practice Leave No Trace and we pack out our poop. That’s not enough anymore. We can all feel the pressure of all the humans in the backcountry. The desire to push our bodies farther and farther out on the land. I like to remind myself that our playground is someone else’s home.

Photo by David Moskowitz – Cascades Wolverine Project

I’ve danced with calling it recreational consumerism. I’m just as guilty as the next, we all are. We all consume recreation to some extent. We’re human, perfectly imperfect. Whether we miss the ice worms while checking our watch to see how many calories we’ve burned or glance over the particular color of blue the ice reflects in the morning sun while we’re contemplating how angry our boss made us. Perhaps you’re stealing a rushed run or bike ride after work and you miss the delicately blooming foxglove swaying in the breeze across the recent clear cut teeming with life after death. Or perhaps you’re thinking about what your partner said or did and you miss the owl sleeping in the tree. Or even worse, perhaps you’re so determined to run your daily 5 or 10 miles, that you ignore just how much your body hurts or how tired you really are. I reckon it’s not only an inability to listen but also an inability to hear.

The Art of Listening

Hearing first requires that you are listening and listening requires that you aren’t talking, out loud or in your head. Listening as a form of offering your attention to someone or something is a practiced skill — perfect for long slogs up a trail or skin track. Listening is only one of our senses. We humans rely heavily on seeing, but we have others – tasting, smelling, feeling, and sensing. The particular taste of the water from the melting glacier, the smell of the sun warming up the forest. A feeling of awe and perhaps grief for the melting glacier, peeled back to its underskin, exposed to the sun for the very first time. The feeling of ancient ice moving under your feet. The joyous sound gear makes clanging on your harness. We can feel the particular way our axe sinks into the ice. That feeling can activate your sense of intuition. Was it a good stick or a bad stick? Your body knows. All of these moments are never to happen again in the particular way you are witnessing and participating with them. All of these moments have secrets to share with you.

Truth be told I initially found it exhausting to participate in the world and recreation this way – engaging all of my senses. It requires me to slow down. These are skills that need exercise and practice, just like crevasse rescue. I’m also not suggesting that you don’t go for the summit and that you don’t push your body. Those moments when you are completely in tune with your body and the climb are equally as important. Wild feats coming to life can surely feed the soul. This art of sensing is a tool to bring your body back into relationship with the land. When you’re on a ridge and the wind is blowing snow in your face, you can’t see a damn thing, and your heart is beating in your head rather than your chest, you are in a critical moment when the earth is likely speaking to you. I’ve pushed through these moments to the summit and I’ve also turned around. You might make a different decision in that same moment. My point is, the conversation is with you and the moment, if you’ll offer your attention.

This is the relationship with recreation I’d like to cultivate. Terry Tempest Williams says it well,

“As a child, I came to understand my relationship to nature was reciprocal and that nature had a relationship with me. We called to one another. We called one another into being.”

I’d like to create a space where people can dream and imagine their own relationship with wild places and recreation and help them tend those imaginings. Offering safe access to recreation feels even more important as the younger generations have less of a relationship with wild places and more of a relationship with their screens. And this is where I always pause and ask myself what are we offering? Are we selling summit attempts? Or are we creating a space where people can perhaps catch a glimpse of their own soul in conversation with the soul of the Earth while also climbing a mountain? Or is it both or perhaps somewhere in between?

Calling Us Home

Not everyone stayed at home during the quarantine, but many did. In the times I did wander beyond the backyard trails, I could hear and feel the sigh of the Earth from somewhere in the deepest caverns of her belly. A sigh of pause and stillness, perhaps of relief even, as the humans (hopefully) sat in reflection, or sheer boredom – but sitting nonetheless, even if just for a few moments. It was so damn quiet. The silence was deafening. Tears of grief and joy were all I could offer in that moment and even that didn’t feel like enough.

It won’t always feel like this. I crafted my first adventure back into the mountains with an ambitious dance up Mt. Baker. I hadn’t summitted since I was pregnant (Josie is three now), I hadn’t tasted mountain air in twelve weeks, I hadn’t felt the glide of my skis on the frozen skin of the earth. I was hungry for mountain time. Admittedly, that hunger overrode my ability to be in deep conversation with the earth on that climb. And again, that’s ok. What did happen was deep conversation with my partners about why and how we were there doing what we were doing. Conversations I couldn’t imagine happening a year ago.

As we all begin to wander back into the backcountry, we might find the desire to run up summits to make up for lost time, we might find the desire to walk slowly up a trail and find a soft place to sit. I’m hoping it’s both. The earth dreams of our feet dancing along her ridges, sitting in the lakes of her belly, and painting the clouds of her skies. Hear the sound of your feet on her skin. Feel the warmth of the sun on your face. Taste the ice turned to water a second ago. Offer your attention to the earth. Dream with her and she will dream with you. Our playground is our home.

“If we approached rivers, mountains, dragonflies, redwoods and reptiles as if all are alive, intelligent and suffused with soul, imagination and purpose, what might the world become?”

“Who would WE become if we participated intentionally with such an animate earth?”

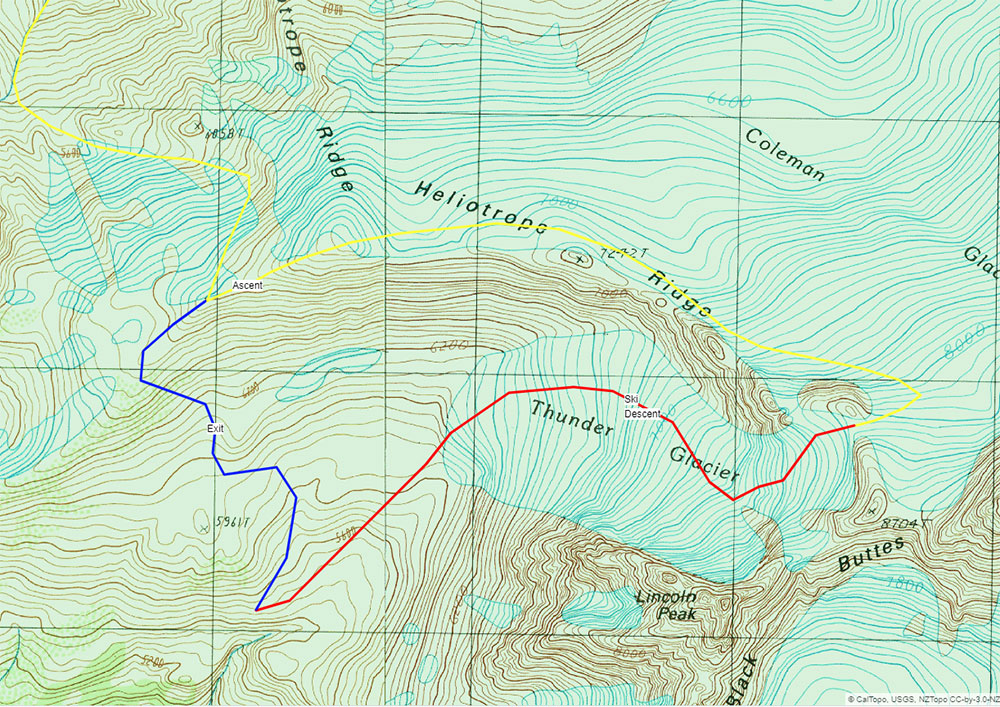

Thunder Glacier

Ski Descent

A Hidden Classic

We’re lucky to have Mount Baker as our namesake and main office. Complex, heavily glaciated, and wonderfully positioned in the North Cascades, Koma Kulshan stands at only 10,781 feet, yet radiates a BIG mountain impression. The mountain receives some of the largest snowfall totals in the world and hosts numerous classic ski mountaineering objectives. I’ve been exploring this topography for nearly four years and it continues to deliver amazing opportunities for adventure, such as skiing the Thunder Glacier.

The Thunder Glacier had been on my radar as a ski descent for several winters. It’s a striking line that’s often hidden while climbing the main routes. The Thunder Glacier is tucked between the jagged walls of Lincoln Peak and Heliotrope Ridge. Both flanks are characterized by crevasses and seracs, leaving a perfectly plumb fall line descent right down the middle. On March 15th 2020, as “normal” daily life was about to come to a screeching halt, we set off to snag what would be one of the last missions of our season.

Glacier Creek Road Access

At 5:00 am the crew piled into my Tundra with snowmobiles in-toe. As we rolled out of Bellingham and down HWY 542, the excitement for the day started to build.I love these big days in the mountains. Forty-five minutes later, we found snowline on the Glacier Creek Road ◙. Five miles remained between us and the Heliotrop Trailhead ◙. Time to unload the sleds and figure out how to get six people up the road with two machines.

We had two options: we could shuttle and do two trips from truck to trailhead or we could double tow and get everyone up in one push. Shuttling would be easier on the snowmobiles and the legs; towing would save us an hour. I have a tendency to get a little over-stoked from time-to-time, especially when we have the opportunity to get the Baker Mountain Guides squad together on a rare sunny pow day. That and the fact that we were heading out for a big day made us decide to tow. A short 15 – 20-minute ride and we’d be on skis heading up the mountain. What could go wrong

This was our first season with consistent access to snowmobiles, necessary toys to execute our new program: Twin Sisters Backcountry Skiing. In efforts to execute a smooth day of guiding on sleds, the past month was dedicated to, well, making mistakes. We learned how to get stuck, get unstuck, rig gear poorly, and rig gear properly. The devil is in the details and we still had a few lessons to learn.

The zone is popular amongst local snowmobilers and the road typically boasts a packed sled track. Packed roads require the use of scratchers. These little rods of metal scratch the firm snow, kicking up enough debris to keep the engine cool. Fueled by excitement, we overlooked these little buggers and took off before putting them down. Nearly halfway, both drivers smelled trouble, literally. The sleds were overheating. We stopped, packed the tracks with snow and waited roughly 20 minutes for things to cool down. The hot engine melted and warped one of the drive belts. With snowmobiles you just have to roll with the punches; they break, get stuck, overheat, it’s just the name of the game.

By 7:30 am we made it to the trailhead. Psyche levels were high.

Coleman Glacier Approach

We left the snowmobiles behind and started the 3000-foot ascent up Grouse Creek ◙ to gain Heliotrope Ridge ◙. The morning was cold and calm as we toured through the old-growth forest. At treeline, we got our first look at the upper mountain. We observed active wind transport off the ridgelines giving us some concern for the conditions to come. However, the protected slopes lower on the mountain harbored perfect cold smoke pow. We continued, knowing that no matter what happened, we’d enjoy some fantastic skiing.

From the top of Heliotrope Ridge the views were amazing. To the south and west, we could see the Twin Sisters Range and the San Juan Islands. To the north, Canadian peaks littered the horizon. The Thunder Glacier was positioned directly in front of us with Mount Baker’s stoic presence looming in the background.

The south wind was stronger than we expected. Fortunately, the jagged spires of Lincoln Peak ◙ provided some protection for the route. Ski mountaineering is a game of margins. The deck was stacked in our favor with an experienced team, clear skies above, and the option to spin at any time. After some deliberation, we decided to continue.

We dropped onto the Football Field ◙, a distinct feature on the Coleman Glacier ◙. Here, we donned harnesses and crevasse rescue gear. Another 1000 feet of climbing brought us to the base of the impressive North Face of Colfax Peak ◙. From here the route takes a sharp right turn off the Coleman for the final push to the top of the Thunder Glacier.

The winds were gusting up to 40 mph with sustained speeds in the 20’s as we crested over the saddle. When we peered down the other side things didn’t add up. We had over-shot the Thunder Glacier by a hundred feet and found ourselves looking out over the Deming Glacier ◙. A short five-minute downward traverse would lead us to the upper headwall of the Thunder Glacier and the proper start of the descent.

Thunder Glacier Ski Descent

12:30 pm. Standing on top of the route it was clear that we needed to avoid the Thunder Glacier’s upper headwall. Excited and nervous, we weighed our options. The snow conditions just weren’t right for terrain that steep. To maintain our margin for error, we skied down the ridge to a saddle 500 feet below. This allowed us to take advantage of a low angle entrance onto the Thunder Glacier.

The skiing on the ridge was pretty bad. Variable and wind affected snow made for an exciting start to the descent. There was still hope that we would find better conditions lower down where the snow was protected from the strongest winds. As soon as we dropped off the saddle and onto the Thunder Glacier, the snow conditions improved. Our smiles grew large in anticipation of the turns to come.

We skied short pitches through some lower angle terrain, feeling out the conditions. As we approached a steeper and more broken section of the Thunder Glacier, a small, shallow wind slab popped on a steep convexity and ran down into a large crevasse. We set up for a long pitch of skiing through the crux of the route. We descended one at a time. It skied like a dream; beautiful boot-top pow down a 35-degree apron in a wild position. Like I said before, I love these big days in the mountains.

Everyone relaxed a bit as we paused below the crux to catch our breath and take it all in. Finally, we continued down the remaining 1,400 vertical feet of nearly perfect, untouched powder only stopping to look back in disbelief at the stunning terrain. For the majority of the line, we were in the shadow of Lincoln Peak. Near the bottom, we popped out into the sun and stopped for a much-needed break to refuel. Looking back at the Thunder Glacier we noticed that almost all of our tracks were gone. The wind quickly reset the landscape and it was as if we were never there. The impermanence of it all – the tracks, our presence – it was perfect.

Before long it was time to pack up and start our final climb of the day. The descent drops you into another basin, leaving a mean 1,200-foot climb back to the top of Grouse Creek. Despite the wind and fatigue, the team made quick work of the climb, fueled by accomplishment. Soon enough, we were transitioning for another 3,000 feet of powder back to the snowmobiles.

Thunder Glacier Route Profile:

- Total Distance – 8.5 Miles

- Trailhead Elevation – 3650 feet

- Top of Route – 8570 feet

- Elevation Gain – 6100 feet

- Thunder Glacier Descent – 3070 feet

Mount Baker

Training Plan

The Mount Baker Training Plan is designed to prepare you to climb Mount Baker, assuming the most commonly climbed route – the Coleman Deming. In general, individuals with an active lifestyle should have the necessary fitness to summit Mount Baker, however, the following training plan will ensure that you arrive well prepared and confident in your abilities.

Having something to train for is motivating. When that ‘something’ involves the outdoors the motivation increases. Why? Because your time in the gym is used to enhance your adventure. The outdoors are uncertain and ever changing. Conditions and events are not ours to decide. Training for the unexpected can keep us pushing through the drudgery.

Mount Baker Training Plan Goals

- Increase your endurance. This will be done through trail running, step ups and hiking / rucking under load (30-40#).

- Strengthen your ‘Mountain Chassis’ (legs & mid-section). The stronger your mountain chassis the more efficient you’ll move.

- Exercises that strengthen those often neglected stabilizer muscles will be included to help decrease your risk of injury and keep your body balanced.

- Increase your mental fitness specific to the demands of your Baker summit.

Mount Baker Training Plan Description

This is an intense, progressive, 7-week program. The demands are high and a prior fitness base is recommended prior to starting. The time commitment is no joke. Organization is a must for success. Training runs Monday through Saturday. Sunday is a total rest day.

All training sessions are designed to be completed in order. If you have to deviate from the schedule simply keep the order and do not skip around. The volume of training increases as the program progresses. Week 7 is used as a taper week.

We want you confident and situation ready. Our hope is that this program gives you a desire to keep your fitness at a level not far from a level to complete any bid that beckons.

Equipment List

- Bench or box for step ups approximately 17” high

- Backpack or ruck sack loaded with 20-45# for hiking / rucking

- Sandbag 40# women / 60# men – an old army surplus bag filled with mulch or pellets and sealed with zip tie and gorilla tape will do the trick

- 10# Iron Plate for dragging / pushing 15# / 25# plate or bumper for rotational mid section work

- Jump Rope

- Pull Up bar

- Small Resistance Bands

- Optional – Counter for step ups / phone app or GPS watch for trail runs, hiking and rucking

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What’s the difference between my hike and ruck efforts?

A: Hiking has prescribed vertical feet to complete. Ruck is over your choice of terrain, and should look like a fast walk / light jog.

Q: What do the first and second number represent after an exercise? i.e Sandbag Get Ups – 40#/60#.

A: First number is the load for women, second for men.

Q: There is only prescribed stretching on Wednesday’s. Should I do more?

A: Absolutely. We highly recommend spending at least 15 minutes on mobility work after every Mountain Endurance / Leg Strength session.

Q: Do you have videos / descriptions of the prescribed exercises?

A: Please see the following videos / descriptions of exercises included in the Mount Baker Training Plan.

Mini Leg Blaster

- 10x Air Squats

- 5x Lunge (each leg, 10x alternating)

- 5x Jump Lunge

- 5x Jump Squats

Full Leg Blaster

- 20x Air Squats

- 10x Lunges (each leg, 20x alternating)

- 10x Jump Lunge

- 10x Jump Squats

Mount Baker Training Plan Sessions

Session 1: Mountain Endurance / Chassis Integrity

1) 600x Step Ups with 25# Pack or Vest

2) 10 Minute Grind

– 5m Plate Drag

– 6x Seated Russian Twist 15/25#

– 6x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 2: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 5:00 Jump Rope

2) 10 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster with 30 Seconds Rest

3) 3.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 3: Chassis Integrity / Upper Body

1) 10 Minute Grind

– 5x Shoulder Taps

– 8x EO’s

– 10m Sandbag Carry 40/60#

– 10/10 Seconds Standing Founder

2) 5 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Ups

– 3x/5x Pull Ups

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

3) 3 Rounds

– 5m Band Walk

– 3x Shoulder Sweeps

– Camel + Frog Stretch

– Pigeon Stretch

Session 4: Mountain Endurance

1) Ruck 5.0 miles with 35# Pack

Session 5: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 10 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster with 30 Seconds Rest

2) Hike 1,000 Vertical Feet with 25# Pack

Session 6: Mountain Endurance

1) 5.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 7: Mountain Endurance / Chassis Integrity

1) 800x Step Ups with 25# Pack or Vest

2) 12 Minute Grind

– 5m Plate Drag

– 7x Seated Russian Twist 15/25#

– 7x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 8: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 6:00 Jump Rope

2) 2 Rounds Full Leg Blaster with 30 Seconds Rest

3) 6 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster with 30 Seconds Rest

4) 3.5 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 9: Chassis Integrity / Upper Body

1) 12 Minute Grind

– 6x Shoulder Taps

– 12x EO’s

– 15m Sandbag Carry 40/60#

– 15/15 Standing Founder

2) 6 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Ups

– 3x/5x Pull Ups

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

3) 3 Rounds

– 5m Band Walk

– 3x Shoulder Sweeps

– Camel + Frog

– Pigeon Stretch

Session 10: Mountain Endurance

1) Ruck 6.0 Miles with 35# Pack – Conversational Pace

Session 11: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 2 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 6 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

3) Hike 1,200 Vertical Feet with 25# Pack

Session 12: Mountain Endurance

1) 6.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 13: Mountain Endurance / Chassis Integrity

1) 1,000 Step Ups with 25# Pack or Vest

2) 15 Minute Grind

– 5m/5m Plate Drag and Push

– 8x Seated Russian Twist 15/25#

– 8x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 14: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 3 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 4 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

3) 4.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 15: Chassis Integrity / Upper Body

1) 15 Minute Grind

– 7x Shoulder Taps

– 14x EO’s

– 20m Sandbag Carry 40/60#

– 20/20 Second Standing Founder

2) 7 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Ups

– 3x/5x Pull Ups

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

3) 3 Rounds

– 10m Band Walk

– 5x Shoulder Sweeps

– Camel + Frog

– Elevated Pigeon Stretch

Session 16: Mountain Endurance

1) Ruck 7.0 Miles with 35# Pack – Conversational Pace

Session 17: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 3 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 4 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

3) Hike 1,400 Vertical Feet with 35# Pack

Session 18: Mountain Endurance

1) 7.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 19: Mountain Endurance / Chassis Integrity

1) 1,200x Step Ups with 25# Pack

2) 17 Minute Grind

– 5m/5m Plate Drag & Push

– 9x Seated Russian Twist 15/25#

– 9x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 20: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 4 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 2 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

3) 4.5 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 21: Chassis Integrity / Upper Body

1) 17 Minute Grind

– 8x Shoulder Taps

– 16x EO’s

– 20m Sandbag Carry 40/60#

– 25/25 Second Standing Founder

2) 8 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Up

– 3x/5x Pull Up

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

3) 3 Rounds

– 10m Band Walk

– 5x Shoulder Sweeps

– Camel + Frog

– Elevated Pigeon Stretch

Session 22: Mountain Endurance

1) Ruck 8.0 Miles with 35# Pack – Conversational Pace

Session 23: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 4 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 2 Rounds Mini Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

3) Hike 1,600 Vertical Feet with 35# Pack

Session 24: Mountain Endurance

1) 8.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 25: Mountain Endurance / Chassis Integrity

1) 1,400x Step Ups with 25# Pack or Vest

2) 20 Minute Grind

– 5m/5m Plate Drag / Push

– 10x Seated Russian Twist 40/60#

– 10x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 26: Leg Strength / Chassis Integrity

1) 9:00 Jump Rope

2) Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

3) 5.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 27: Chassis Integrity / Upper Body

1) 20 Minute Grind

– 9x Shoulder Taps

– 18x EO’s

– 20m Sandbag Carry 40/60#

– 25/25 Standing Founder

2) 9 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Ups

– 3x/5x Pull Ups

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

3) 3 Rounds

– 10m Band Walk

– 5x Shoulder Sweeps

– Camel + Frog Stretch

– Standing Pigeon Stretch

Session 28: Mountain Endurance

1) Ruck 9.0 Miles with 35# Pack – Conversational Pace

Session 29: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 5 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) Hike 1,800 Vertical Feet with 35# Pack

Session 30: Mountain Endurance

1) 9.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 31: Mountain Endurance / Chassis Integrity

1) 1,600x Step Ups with 25# Pack or Vest

2) 20 Minute Grind

– 5m/5m Plate Drag & Push

– 10x Seated Russian Twist 15/25#

– 10x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 32: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 5 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 5.5 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 33: Chassis Integrity / Upper Body

1) 20 Minute Grind

– 10x Shoulder Taps

– 20x EO’s

– 20m Sandbag Carry 40/60#

– 25/25 Second Standing Founder

2) 10 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Ups

– 3x/5x Pull Ups

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

3) 3 Rounds

– 10m Band Walk

– Elevated Pigeon Stretch

– 5x Shoulder Sweeps

– Camel + Frog Stretch

Session 34: Mountain Endurance

1) Ruck 10.0 Miles with 35# Pack – Conversational Pace

Session 35: Leg Strength / Mountain Endurance

1) 5 Rounds Full Leg Blaster – 30 Seconds Rest

2) 1,800 Vertical Feet Hike with 35# Pack

Session 36: Mountain Endurance

1) 10.0 Mile Trail Run – Conversational Pace

Session 37: Mountain Endurance

1) 600x Step Ups with 25# Pack or Vest

2) 10 Minute Grind

– 5m Plate Drag

– 5x Seated Russian Twist 15/25#

– 5x Sandbag Get Ups 40/60#

Session 38: Mountain Endurance / Upper Body

1) 3.0 Mile Trail Run

2) 5 Rounds

– 3x/5x Chin Up

– 3x/5x Pull Ups

– 5x Strict Knees to Chest

– 8x Band Shoulder Dislocates

Sessions 39-42: Rest

Tonia Boze founded Terrain Gym in 2007 as a strength and conditioning facility to specialize in training athletes specifically for their sport or profession.

Tonia Started working in the fitness industry in 1996. Certifications / Seminars include – Mountain Athlete Coach, Mountain Tactical Institute Advanced Programming, Catalyst Athletics, USA Gymnastics National Congress, Primal Blueprint Nutrition Coach, Precision Nutrition Level 1 Coach, BioForce Conditioning Coach, BioForce HRV, CrossFit Level 1.

2016 Mountain Guide Training

Guide Training Recap

Our 2016 Spring Mountain Guide training is in the bag! After a long and productive week, it seems appropriate to reflect, and offer up some thoughts on the experience.

As it turns out, Google Analytics is good for something. One of the most visited pages on bakermountainguides.com is our About Page – and rightfully so. Our clients want to know who they are going to be climbing or skiing with. When you choose a guide service, you aren’t so much hiring a guide service as you are hiring a specific guide. Ideally that guide has been vetted, and reflects the culture and standards of the organization he or she works for.

In the United States, the American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA) provides 3rd party training and certification for mountain guides. The process is rigorous, and full certification (IFMGA) requires tens of thousands of dollars as well as a multi-year commitment. However, in the US, certification is not a requirement for employment. Often the best guides have a combination of AMGA training/certification as well as hands-on experience and mentorship.

AMGA Guide Training Disciplines

At Baker Mountain Guides we specifically hire guides who have a proven commitment to AMGA training and certification. All the guides that we employ regularly are either pursuing or currently hold a certification through the AMGA. Additionally, we offer Continuing Professional Development Credits to assist guides with AMGA tuition.

However, it’s also important for guides to understand who we are as an organization, and what our expectations are. Our in-house guide training provides us with the opportunity to orient guides to our operation, refresh and assess critical skills, and provide valuable feedback to help our guides develop in their profession. This year’s training involved 5 days of field time in both rock and alpine environments with Lee Lazzara – our senior IFMGA guide and guide trainer.

Lee works with several well-respected organizations, and guides in Europe during the summer months. He also runs a guide training for several Northwest Guide Services. He designed a Baker Mountain Guides training program to cater to our specific needs. Again, the purpose wasn’t to teach our guides how to guide – that is better left to the AMGA – but to teach them how we would like them to guide in the terrain that we most commonly operate in: Mount Baker.

Our guide training fell into the context of client care and risk management. Objectives included short roping on both rock and snow, which is a professionally oriented technique not common among recreational groups. Much attention was paid to alpine transitions as well, which is essentially the art of moving between different rope systems and guiding techniques based on terrain and hazards. The program finished with both crevasse and rock rescue refreshers.

As always, Mount Baker was an excellent training environment. Ironically, we chose not to summit Baker, but opted for the East Ridge of Colfax instead. The East Ridge of Colfax is a more challenging objective that forces guides to think outside the box. The Coleman Deming route on Mount Baker would have been a better preview of a common route that we guide, but we are less concerned with our guides knowing a specific route, and more concerned that they have the skills to manage hazard and guide effectively in any terrain that they encounter.

We finished up on Baker with a Crevasse Rescue refresher where we reviewed professional level techniques. Any guide in any glaciated terrain should be very comfortable performing crevasse rescue. Terrain assessment, hazard ID/mitigation, and client care are areas where all guides can improve, however anything less than full fluency in crevasse rescue is unacceptable.

Our Baker days were sandwiched between two sessions on the cliffs at Mount Erie in Anacortes, where we covered short roping on rock, alpine transitions, and rock rescue. The rock rescue drill that we practice prepares guides to evacuate an injured climber from a vertical environment. This situation is rare, however, working through the challenges of rock rescue prepares guides for problem solving in any technical rope system. Again, the purpose is not to teach a specific drill, but to prepare guides for any terrain or situation they may find themselves in.

The result is a team that is well indoctrinated not only to Baker Mountain Guides terrain, but to our culture as well. Training is an important aspect of professionalism in our industry, and all our guides are qualified to operate in the terrain in which they are guiding. Hopefully this post provides some insight into the inner workings of our industry, as well as our approach to pedagogy. These are concepts that we carry over into our guided trips and instructional courses as well. We invite you experience the Baker Mountain Guides difference, and climb with a member of our fantastic crew!

Reflections from the Rope Line

Greg Morgan climbed Mt. Baker as a guest with Baker Mountain Guides. He has written a thoughtful account of his experience on his personal blog, and graciously permitted us to share and re-post his words here. To read more of Greg’s writings, please visit his Blog: Midlife Sabbatical

One of my great delights this summer has been a climb of Mount Baker (10,781’) in northwest Washington, a mountain that one guide book describes as “pound for pound, the iciest of the Cascade volcanoes.” My climb was blessed by fabulous companions, expert guides, and perfect weather, and it left me with wonderful memories that will be food for joyful reflection for years to come.

The journey from base camp (around 6,000’) to the summit is really just a long walk, requiring no rock-climbing skills. The catch, of course, is that the route is over snow and ice virtually all the way, in places quite steep, and much of it over the top of an active glacier. The use of an ice ax and crampons (snow spikes attached to one’s boots) are essential, and we were roped together in teams of four for the entire duration (except for on the broad, flat summit). A few interesting reflections rose for me as I climbed and descended this mountain in unison with the three other companions on my rope line.

The chief purpose of the rope line was captured perfectly in the book of Ecclesiastes more than 2000 years ago: “Two are better than one, for their partnership yields this advantage: if one falls, the other can help his companion up again” (Eccl. 4:10). And four are better than two, for if one falls there are three to help. We had all practiced self-arrest techniques the previous day, in which the ice ax is used to stop a slide on steep snow. But one’s confidence is increased immeasurably by knowing that others are there to help break any such fall and help out as needed. It is much easier to attempt new goals that feel risky when one is surrounded by community.

For much of the climb we were “on the long rope,” separated from each other by thirty feet or so (as pictured above). Most of the rope between any two climbers should glide along the surface of the snow in a straight line, with no excess slack. Each climber should be able to move fairly independently, but the rope should become taut immediately in the event anything unexpected happens. This tension is never maintained perfectly, but we were taught the motto “better to be a jerk than a slacker.” The lesson I take from this: when living in a community, maintaining space and boundaries are important, but it’s better to be in a little too frequent contact than to drift apart and lose touch.

During one long, easy part of the descent, I was in the lead position on the second rope. My companion Bruce was in the back position on the first rope, close enough to begin a conversation. We drew closer to each other to be able to speak more easily, but the guide on my rope called out “Greg, maintain the same distance from Bruce as we are keeping between those of us on this rope.” I replied, “Will do, but I am curious as to why.” He replied, “This is an active glacier, and one can never tell for sure when one might be walking on a snow bridge over a crevasse. We never want two people walking over a snow bridge at the same time – it increases the risk of a bridge failing, as well as the consequences.” Clearly, sometimes there are more reasons than we realize for maintaining healthy spacing between us!

Still, there are also times for pulling together more closely, and in climbing this is called “short roping.” In this technique, the climbers have only about eight feet between them, and the goal, in the words of our guide, is to “behave as a single organism.” The rope has little slack, so that any slip can be stopped quickly. We used this technique when climbing “the Roman Wall,” a slope of snow that increases from a 20% grade to 40% in the course of ascending 800 vertical feet. We moved with synchronized steps, each climber utilizing the prints of the person just ahead to ensure good footing. We found a pace that we could all sustain comfortably, and then we ascended steadily—as one organism.

One climbing site opined that the chief advantage of this method is psychological: “Short-roping greatly increases the climbers’ confidence. As a result they are more relaxed and concentrate better on secure footing, thus greatly reducing the probability that they fall.” This accurately described my own experience, especially during the more challenging descent of the Roman Wall, where I was in the lead—the comforting, encouraging chatter from my rope-mates right behind me really settled my nerves and helped me focus on placing my feet and ice ax. The immediate tug of the rope I felt on the one or two occasions where I slipped a bit reminded me of the extra security my companions were providing me and further enabled me to be a better climber. As one living, breathing, communicating, moving organism, we descended safely down the steepest pitches of the wall and back to easier terrain.

Life on the short rope, or any rope—literal or figurative—can only be sustained comfortably for so long. We all instinctively desire independence in our movements and actions, so it felt good to move back to the long rope after completing the steepest part of the descent, and even better to shed the ropes completely once we got off the snow. We also feel best living in a place with sufficient security that such protective measures aren’t generally necessary, so, as always, I began to breathe a little more easily once I returned to the comforts of civilization.

Knowing how many people in the world today live without the basic security I enjoy, I recognize what a luxury it is to be able to undertake such adventures voluntarily. But I am nonetheless grateful for the opportunity this climb provided me to experience living in close community in an entirely different way. And I don’t need to stay tied in to a rope line in order to try to apply these lessons to living in community every day.